November 9, 2025, is the 87th Anniversary of Kristallnacht

In the dark hours of the night of November 9, 1938, a Nazi-instigated pogrom (a violent attack on an ethnic or religious group with the aim of massacre or expulsion) erupted across Germany and Austria. This intense violence against Jews and the destruction of Jewish property lasted for more than twenty-four hours. Known as the “Night of Broken Glass,” or Kristallnacht, this episode is often cited as the true beginning of the Holocaust.

The pogrom was conceived and executed by radicals within the Nazi party. They used the shooting, and subsequent death, of a minor official in the German embassy in Paris by a Jewish teenager as an excuse for the uprising. Nazi stormtroopers disguised as civilians spearheaded the operation. As the mayhem continued, they were soon joined by many regular citizens.

Between Nov. 9 and November 11, more than 36,000 Jewish men across the country were arrested and sent to the prison camps at Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen. Close to a quarter of those imprisoned in this way died from the brutal treatment in the camps. Most of the rest were released, often only when they promised to emigrate immediately. Additionally, during the violence of Kristallnacht, close to 100 Jews were murdered, many more were injured, and at least 300 committed suicide. While police and firemen stood by and did nothing, more than 200 synagogues were burned and ransacked, and thousands of Jewish-owned shops were looted, destroyed, and covered in hate graffiti.

Though the perpetrators of the violence and destruction were not arrested or punished, men who raped Jewish women during Kristallnacht were arrested for miscegenation (the crime of interracial sexual relations). After it was over, Jewish-held insurance policies and Jewish organizations were forced to pay for all damages.

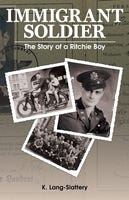

In remembrance of Kristallnacht, I offer the first pages from my novel, Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy. Based on the true story of my uncle, the novel combines a coming-of-age story with an immigrant tale and a World War II adventure. This excerpt recounts the Kristallnacht experiences of Herman, the story’s hero.

TO READ the full book, Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy, take advantage of a special discounted price of $13 good for the month of November.

Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy

(The first two chapters)

THE QUIET OF THE EARLY November morning was shattered by loud voices and the screech of brakes. Herman peered through the crack in the stable door. A prickle of fear shot up his neck at the sight of a covered truck, two police motorcycles, and a black sedan in front of the homes across the street. Two brown-shirted SA officers, the Swastika symbols blazing on their armbands, pounded on his cousin’s front door.

Hatred rose in his throat. Nazi Storm Troopers—they were nothing more than thugs, bullies for Hitler and his political party. Two more men in ugly brown uniforms beat at the door of the neighbor’s home where Herman rented a room from the horse dealer and his wife.

The faces of the SA men contorted with anger, and their words polluted the air. “Achtung! Alles’raus! Attention! Everyone out! Get out, you stupid Jews. Wake up! Schnell! Juden! Alles’raus! Schnell! Fast! Jews! Everyone out! Fast!”

The thud of Herman’s heart was palpable. Pain seized his gut. The door of his landlord’s home opened a crack. One of the SA men kicked it wide, and the loud smack of his boot against the wood sent a chill down Herman’s spine. As the Nazis pushed into the house, he heard the confused sounds of loud voices and smashing furniture. An image of the horse-dealer’s wife, beautiful Frau Mannheimer, exploded in his mind, her nightdress ripped, her golden hair gripped in the SA man’s fist. He heard her high-pitched scream leak into the cold morning, and he lurched forward, outside the barn.

He was barely through the stable door when a policeman stepped from behind the black truck. His pistol glinted in the gray morning light, and the sight of the weapon shocked Herman like a jolt of electricity. His wild impulse to be a hero evaporated. He ducked behind the wide doors, angry and ashamed, listening to his heart pound. He pressed both hands against his abdomen and took several deep breaths.

He shook his head to clear it and again put his eye to the crack between the door and the jamb. The policeman must have heard something because he waved his pistol menacingly. He was poised in a half crouch, as if ready to run, and his gaze swept past the stable, down the street, and back again. Finally, he turned and moved toward the open door of the Mannheimers’ home.

Herman inched farther back into the shadows and waited. Less than an hour ago, he had walked to his morning job, the feel of the street cobbles solid and familiar under his feet, his breath visible in the cold air. In the stable yard, blades of stubborn, frost-crusted grass pushed through the trampled earth. He had dipped his fingers into the water trough, breaking the thin film of ice that glistened in the dawn light. The black surface of the water mirrored a reflection of his gray eyes, strong chin, and the curl of dark hair that fell over his forehead. He pushed back the loose hair with his wet fingers and entered the barn.

The warm odor of straw and manure enveloped him. The powerful draft horses moved in their stalls. The soft stamp of their hooves and the bump of their flanks against the boards comforted him like a morning lullaby.

Herman had gone to the tack room to get the curry brush. His motorcycle, which he was allowed to park there, gleamed amid the coils of rope, harnesses, and bridles. He ran his fingers across the shiny black fender, up the rounded shape of the gas tank, and whispered, “Good morning, baby.” For two years he had saved every pfennig, until finally six months ago, as a celebration of his eighteenth birthday, he had gathered his savings and bought the nearly new motorcycle from a local man bound for the army.

Riding gave him a sense of freedom he couldn’t get from any other part of his life. On his days off work, Herman left the cobbled lanes of Suhl and escaped to the countryside, riding from early morning until the long afternoon shadows bled into dusk. At the crest of a hill, he would hesitate, then with a twist of the throttle, speed forward. The sensation when he swooped down the hill lifted his spirits. Sometimes, if the road was straight and flat, he would let go of the handlebars and stretch his arms out on either side like a tightrope walker. The wind pushed against his hands, tugged at his jacket, and battered his face. For a moment, he could imagine he was fleeing this horrible new Germany. On his way home, as day faded into night, the single head-lamp dimly illuminated the road ahead. He felt like a man returning to prison.

Now he stood in the darkened barn and listened to the muffled sounds that came from outside—the thud of boots, the slam of doors, and shouts of “Raus!’Raus!” Above everything, he heard the heartrending sound of a woman screaming, “Nein, bitte . . . nien, tun Sie ihm nicht weh! Don’t hurt him!” He edged forward cautiously and looked outside again.

His cousin’s wife, Hilda Meyer, normally neat and proper, stood in the street in her night clothes, her robe half on, half off, its belt dangling. Her hair stuck out at odd angles, uncombed and tangled from sleep. She moaned as her husband, still in his pajamas, grasped her shoulder, trying to steady her. He moved one hand to cradle her chin and leaned forward to talk softly into her ear. Cousin Fritz, usually funny and full of stories, was serious now. The words he whispered seemed to calm his wife. Herman could see the movement of shadows in the house doorway, and he knew that little Anna huddled there. An impatient SA man clutched his baton and stomped over. He yelled as he prodded Fritz in the ribs with his club. The controlled look on his cousin’s face dissolved, and his eyes grew wide with fear. The storm trooper took no notice and shoved his victim toward the truck. The whack of the stick against Fritz’s back as he scrambled up into the vehicle was muffled by distance, but the sight made Herman flinch as if he had been struck himself.

Two other SA men emerged from his landlord’s door, the horse dealer between them. Herr Mannheimer was shoeless, the long tails of his unbuttoned shirt flapping in the chilly breeze. Blood streamed from a cut over his eye, dripped down his cheek and neck, and soaked into his shirt collar. He seemed dazed, only half conscious, as he clambered into the back of the truck where Fritz grabbed his neighbor to steady him.

The horse-dealer’s wife was nowhere to be seen. Herman bit his lip and closed his eyes as he tried to imagine her hidden safely in the cupboard under the stairs, but the picture that surged into his head was of her body sprawled on the entryway floor, an SA man, his club raised, towering over her. He opened his eyes allowing the stark reality of the street to erase the image.

Herman saw the flash of Anna’s nightdress as she darted out of the doorway, into the street, and clutched at her mother’s thin flannel dressing gown. The little girl buried her face in her mother’s stomach. Hilda’s shoulders shook, and she released an audible moan as she encircled her daughter with her arms.

The sudden thought of his own mother, alone in their home in Meiningen, pushed Herman into action. He jerked away from the barn door and lurched into the tack room. With one kick of his boot, he flipped up the stand of his motorcycle, struggled to wheel the heavy machine into the stable, and with a last glance toward the wide doors facing the street, pushed it out the back to the paddock and a little-used dirt alleyway. With a practiced swing of his leg, he mounted and kicked the engine to life. The powerful machine took off with a surge of speed that lifted the front tire as it jumped over the first ruts. Icy wind blew his cap from his head, but he raced on. The frigid air stung his ears and drowned out the sounds that echoed in his head. He forced himself to think only of getting home―fast.

HERMAN SPED DOWN THE NARROW lane, only half aware of the passage of time. His mind swirled around a vortex of fears and questions. Were the storm troopers pounding on doors only in the little industrial town of Suhl? Was his hometown involved? How bad would it be? What should he do?

He knew it was finally time for him to make a move, but he had no idea how to escape. He was without a passport and no longer considered a citizen of the German nation. He had been declared a Jew, even though he had never worn a yarmulke, lit a Hanukkah candle, or set foot in a synagogue. He knew nothing of Jewish culture or religion, but all four of his grandparents had been Jews long ago, and now that was all that counted in the Third Reich.

The road twisted and turned under him as he sped toward home. He forgot his own safety until he felt the front tire slide in the gravel on a stretch of soft shoulder.

Herman struggled to steady the cycle and forced himself to slow down and think. He could simply veer off the road and disappear into the countryside. The peaceful farms beckoned to him. He could sleep in the stacked winter hay of a barn at night and hide among the tall forest trees during the day. Maybe he could escape to Switzerland, cross the Alps into Italy, and make his way to North Africa, where he would join the French Foreign Legion like the heroes of the books and movies he loved.

Herman shook his head to expel this wild plan, but he could not shake the worried thoughts from his mind. Italy was ruled by Hitler’s Fascist allies. Besides, winter was coming. Freezing temperatures and mountain snow would leech success from an attempt to cross the Alps. And what about his mother? His daydreams came to an abrupt stop. He could not go anywhere without first making sure she was safe. After that, there would be time to try to get a passport and an exit permit, make a sensible plan, and figure out how to survive. Nazi law prohibited Jews from taking money with them if they fled. He tried to concentrate, but there was too much to think about. Could he join the Foreign Legion? How would he pay for passage to North Africa? Could he find work on a tramp steamer? One thing he knew for sure—it was past time to put aside his doubts and leave Germany.

As he neared Meiningen, the road circled the familiar castle-topped hill and approached the Werra River. The steel gray waters of the river slid slowly past the brewery, which used the waterpower to run its machinery. Herman felt his gut tighten. A knot of tension sat heavy in his belly. He slowed the rumbling machine to a workday pace, straightened his shoulders, and surveyed the street ahead for any sign of a police vehicle. He eased past a group of men who had arrived at the brewery gate for the morning shift and started across the wide bridge that spanned the river. His gaze was pulled to the Duke of Meiningen’s palace where the familiar white walls gleamed through the bare trees of the royal park. Behind the palace, an ominous cloud of black smoke rose above the walls. Something burned in the old Jewish section where his grandmother had lived. Two laborers in coveralls paused on their way to work. They pointed toward the smoke, laughing and slapping each other on the back.

He rode slowly across the bridge into town and onto the busy main street that led to the downtown shopping district. Everything seemed normal. A meat delivery wagon maneuvered around a streetcar filled with office workers and shop girls and past the English Garden, where he had often played as a child. Herman gunned the motorcycle and made a right turn from the busy street through the double gates of his family home directly across from the garden. He skidded to a stop in the yard and looked around for anything out of the ordinary. All seemed quiet. He quickly hid his cycle up against the wall behind a hedge and ran up the porch stairs. Relieved to find the big front doors already unlocked, he slipped noiselessly into the entry hall, then bolted up the wide stairs, two at a time, to his mother’s apartment. In this grand home, where she had once raised three children and directed housemaids and a cook, she now lived, widowed and alone, in a small, converted apartment squeezed into half of the second floor. At least she had the tower room overlooking the street. “It is enough,” she had said, “for one very small woman.”

His mother, Clara, though less than five feet tall, had a solid spirit that had always given him comfort. She waited on the landing, her dressing gown loosely tied. Herman could see she had not been awake long. One swath of her hair still hung below her waist, and the dark brown sheen of it caught the morning light. She had only managed to get the other portion of her hair half-braided, and it draped over her right shoulder and across her ample chest. She clasped the loose end of the braid with one hand and reached out with the other to touch her son. “I saw you through the window,” she said, her look steady and calming. “I’m glad you came home.”

Herman, taller than his mother by five inches, enveloped her in his arms. “You’re safe,” he whispered.

“Certainly I am.” She wrapped her free arm around him protectively. “Come inside. We don’t want to linger on the landing this morning.”

Herman entered the apartment, closed the door, looked around at the familiar furniture and pictures, and turned to his mother. “Mutti, something terrible is happening. I left in such a hurry, I didn’t think about anything except getting here to make sure you’re safe.”

His mother carefully turned the bolt on the door. “Of course I am safe.” She slowly finished the braiding of her loose hair as she talked. “I’ve been listening to the radio and the news is bad. It’s you . . . the men . . . who are in danger.” Herman grasped his mother’s hands. “I saw Fritz and Herr Mannheimer being taken. They dragged Fritz directly from bed and into the street. He was still in his pajamas. I saw them beat him.” He sank into a chair. “Herr Mannheimer was worse. His face was covered in blood.” He brushed away tears that threatened to roll down his cheeks. “I should have helped. Oh, Mutti, I didn’t know what to do.” He slumped in the armchair and lowered his head,

his hands over his eyes. His mother grasped his shoulder and with her other hand, firmly lifted his face to meet her gaze. “No,” she said. “There was nothing you could do. You were right to come here.” She turned away and stood by the window but did not pull open the heavy drapes. “Fritz will be all right.” Her voice was firm. “And the horse dealer, too.”

“But Hilda. And Frau Mannheimer.” Herman’s voice broke as he said their names.

She turned back toward her son, and her hand brushed his cheek. “Hush. The women and children are probably safe. It’s the men . . .” Her next words were barely a whisper. “Together we will make it through.”

They huddled all morning in the gloomy apartment,

listened to the radio, and talked in low tones until midday, when their friends downstairs slipped a newspaper under the door. The front-page story proclaimed that the erupting violence against Jews and destruction of Jewish property all over Germany was spontaneous, justified anger over the murder of a man named Ernst vom Rath, a Third Secretary of the German embassy in Paris.

Herman sat wrapped in a blanket in his father’s old chair. The same news droned endlessly on the radio. His head felt dull and a muscle in his temple twitched. He reached over and switched the sound off. “Why, Mutti? It doesn’t make any sense.” His voice broke and he closed his lips to keep his fear inside.

His mother shook her head. “Nobody cares about this man or his killer. It’s an excuse.”

“The boy they’ve arrested is my age,” Herman said. “It sounds like he’s half-crazy because of the deportation of his family to Poland.”

“He’s Jewish. That’s all the excuse they need.” Clara walked over to where Herman sat and touched his shoulder gently. “You must stay out of trouble,” she said.

Suddenly, the strident ring of the telephone intensified the tension. Herman’s mother strode quickly to where it sat on a hall table but hesitated with her hand on the earpiece as it rang a second and third time. “You must never answer it,” she whispered. “No one can know you are here.”

Slowly she raised the instrument to her ear and spoke into the receiver. “This is Clara.” She motioned to Herman to come over and stand with his head close to hers, so they could listen together. She mouthed the words, “Cousin Renata.” He could hear the faint sound of the old lady’s sobbing through the earpiece.

“They took him away . . . my strong Morris, but his heart is weak. He could do nothing to resist.”

Clara’s voice was low next to Herman’s ear as she tried to calm her cousin. “Don’t worry, Renata. All will be well. In a day or two he will return.”

Herman felt his mother’s tremor of doubt.

The voice in the phone rose, the edge of hysteria clear. “What will he do without even his trousers? Only his nightshirt. Barefoot. He will be cold . . . and his heart medicine still beside his bed. I’m terrified. I must go to the police station with his coat and shoes, but all I do is stand here and cry.”

“Be calm. Steady yourself.” His mother tried to make her cousin slow down but she could not hear beyond her own voice.

“And the synagogue! In ruins. Still smoking. I can see it from my window.”

“Stop! Listen now!”

Finally, Renata’s voice was quiet.

“Make a bundle of the coat and shoes and Morris’s medicines. Pull yourself together and go to the station. Doing something will calm your nerves.”

“Yes. Yes, you’re right.” There was a deep, shuddering sob on the phone line. “I’ll try . . . I must try.”

“Call me back this afternoon . . . or any time.”

“Clara, what of Herman?”

His mother laid her finger to her lips and shook her head. “No word from him,” she said into the phone. “But he is resourceful. I know he will be safe.”

“Yes. Herman is a strong boy. I must go now . . . I’ll call again.”

The radio news announced that Jewish men were being pulled from their homes and arrested everywhere in Germany. Repeatedly, Clara tried to telephone Great-Uncle Martin who still lived in the old Jewish section of town, but his phone went unanswered. As the day progressed, the news worsened. Jewish shops were being vandalized and looted. Synagogues across the country burned to the ground while firemen stood by and watched. It was a full-fledged Nazi pogrom.

Herman reminded his mother that the Meiningen police didn’t know he was at home, and if no one saw his early morning arrival, it would be assumed he had been picked up where he had been living. In Suhl, maybe they hadn’t noticed he wasn’t among the arrested, or they simply didn’t care. The family home in Meiningen wasn’t in the Jewish section of town and nowhere near the synagogue. The police had pounded on the door at other times, including several visits in 1936 and 1937—days when they confiscated silver and other valuables—but this day, as Herman huddled in his mother’s small rooms and wondered at the evil in his homeland, the police didn’t knock.

LATE THAT NIGHT, HERMAN returned to where he had abandoned his motorcycle. He lifted the kickstand and straddled the heavy bike, then started the engine as quietly as possible. Slowly, hoping the sounds blended with the noises of late-night buses on the nearby main street, he rode to the back garden, a narrow space between the house and a high brick wall. He pulled a flashlight out of his pocket and turned it on. Its thin beam of light revealed what he looked for—an old, windowless toolshed leaning against the garden wall, overhung by the branches of a fir tree. The dilapidated shed was small, and the roof probably leaked, but in the winter to come no one would need the garden supplies stored there.

Herman parked the cycle near the shed, turned off the engine, and entered, flashlight in hand. He brushed away tendrils of spider webs, stacked a few buckets and a half-filled bag of manure in the far corner, and shoved two hoes, a shovel, and a rake behind a pile of broken terracotta pots. There would be barely enough room. Outside, he straddled the cycle, then with difficulty, maneuvered it backward through the door, carefully turning and cramping the front wheel to make it fit. He positioned the cumbersome motorcycle so it faced the shed door. He knew the effort might save his life. If he ever needed to get away fast, he would be able to get it out and started in a matter of minutes.

In a last gesture, he rubbed his hand across the bulbous gas tank and gave it an affectionate pat. He closed the shed door and turned away. The darkness enveloped him. He walked up the front stairs of his home and into hiding.

Special Offer

To continue reading Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy, buy your own copy now. For the month of November, I’m offering the paperback at a special discounted price of $13. Offer good until November 30.

If you prefer to read in a digital format, the eBook of Immigrant Soldier is available on Kindle ($7.95) and is currently included for subscribers of Kindle Unlimited.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply