Mexico, September 1971

TOM AND I WERE ONLY a few weeks into our honeymoon road trip. It was late afternoon on our second day in Mexico, and we were sweaty and tired from the long, hot drive across the Sonora Desert. The city of San Luis Potosí slumbered under the siesta-time September sun. Though it was almost 4:00, there were hours of daylight left. Perhaps we could find a better place to spend the night than yet another paved, trailer-park-like, municipal campground. We drove on into the flat, agricultural expanse south of the city. We had begun our trip searching for adventure, and we were about to have one.

Tom and I were both eager to begin free camping in the idyllic spots we imagined waited for us just off the main highway. We scanned the passing landscape for a promising side road. Finally, we saw a cluster of trees in the distance and an off-ramp that encouraged Tom to veer the van onto the exit.

Before the trees, we came to a village. The narrow asphalt road became a cobblestone lane lined with low adobe homes and simple shops. Little girls in faded dresses waved and giggled as we passed. Boisterous boys, their smiles gay behind smudged faces, ran alongside the crazy gringo van heading nowhere. One brave youth hopped on our rear bumper and rode there, triumphantly waving his arms and shouting to his compadres, until we reached the edge of the village. I grinned at Tom. We were on an adventure now!

The cobblestones disappeared. The road was now little more than a rutted lane of hard-packed dirt, and plumes of dust billowed behind us. The warm glow of the late afternoon sun turned the corn and bean fields golden.

There were no streetlights here. Indeed, there were none in the village. When the sun set and night fell, everything would be dark in a way only a place without electricity can be. We needed to find a quiet spot to park soon—someplace safe and level and far enough from the village to discourage the curious local boys. What we found was another village, also long and narrow, and populated by children kicking a soccer ball around the plaza and women who peered out from shade-darkened doorways.

After the last adobe hut disappeared behind us, the dirt road began to run parallel to a stream. The water tempted us to pull over, but the shoulder on one side was boulders and cactus, while, on the other, there were only sandbars and the stream. There was no place to stop. No widening of the road. The trees had disappeared behind us. Ahead there was only rocks, cactus, and prickly scrub.

There was nothing to do but keep driving. On the far side of the stream, I glimpsed a row of trees and more fields. Suddenly I caught a blur of movement. Barely visible in the distance, something was moving fast, and it looked like a truck. “Look! The highway’s over there.” I pointed toward another moving truck. “Perhaps this road will come around to meet up with it.”

Tom glanced over. “Good eye,” he said. “I hope there’s a bridge so we can get to the highway again.”

The flash of moving trucks remained elusive in the distance, and no bridge appeared. The narrow road continued without a shoulder or intersection, without a farmhouse or another village. There was no place to safely settle in for the night.

Unexpectedly, Tom stopped the car near a place where the road dipped down and was almost level with the river. Without a word he got out and walked into the stream, inspecting one sandbar after another until he was almost across the river. He stomped his feet to test the surface. He returned to the bank, pulled a twisted tree branch out of the sand, walked back to the middle of the stream, and probed the depth of the water and the firmness of the sand. Typical of desert rivers, the watercourse was wide, sandy, and flat. What water there was flowed slowly and spread out into rivulets and pools. The opposite bank was a low, gradual incline that looked firm enough. I could see where Tom’s thoughts were leading him.

“The river bottom feels solid,” he said when he got back into the car. “I think we should make a run for it. If we don’t slow down, we should be fine. Are you okay with giving it a try?”

I was willing to do whatever Tom suggested. He knew cars and was an excellent driver. I had agreed to a two-year journey, and after the previous day’s boring drive through the desert, I was ready for something exciting. The challenge and uncertainty of crossing the stream made me feel giddy.

Tom looked at me, his eyes asking for permission. “Ready?” he asked. When I nodded, he put the van in gear and headed onto the sand. Splashes of water sprayed out on either side as we hurtled forward. He gunned the engine and did not slow down when we reached the far bank. The van lurched forward, then hesitated. Loose, dry dirt crumbled under our front tires. We were halfway to solid ground when the rear wheels started to spin uselessly, digging into the wet sand along the edge of the stream.

We were stuck, but I was confident that Tom, an engineer, would find a solution. All I needed to do was support him and help in any way I could.

He climbed to the roof of the van and retrieved our collapsible shovel. “Find me a couple of rocks,” he called as he shoveled sand from around the tires. “Not too big. Flat, if possible.”

I located rocks and lugged them one by one to where Tom knelt in the water behind the van, scooping away wet sand with his hands. He laid my stones under the tires. “Traction,” he said. “I’m going to try again. Stay on the bank out of the way.”

I watched as his efforts pushed the tires deeper into the sand, the rocks disappearing underneath. Now the rear engine rested on the stream bottom, and the exhaust pipe was under water. Tom was behind the van again. Sand and mud flew as he dug a channel to divert the water away from the engine compartment. I watched the muscles of his back ripple under his sweat-dampened shirt and remembered their feel under my hand the night before.

It had been several miles since we had passed the last village. We thought the quiet countryside was unpopulated, but from somewhere a group of men appeared. On their way home from a day working in the fields, they came over to see what kind of trouble these two strange gringos, one a young blond woman, had gotten themselves into. They gathered around Tom as he continued to dig a trench to divert the water. One man spoke in rapid-fire Spanish, which we couldn’t understand. Using gestures and his limited Spanish, Tom tried to explain what he was doing. A couple of the men headed toward a distant hut and soon returned with shovels of their own. They waded into the water and set to work, shoulder to shoulder beside Tom.

I stood with a gaggle of village children who had appeared. We watched the diggers create a channel to direct the water away from our beleaguered van. Tom looked up at me, relief softening the tense muscles in his face. He was glad to have help, and the local men were energetic diggers. He paused to wipe his sweaty brow. “Katie,” he called, “can you lighten the weight on the rear? Empty the water tank first and move our food stores to the front?”

I turned on the water faucet in the sink and watched our precious purified water gush from our tank, down the drain, out the side of the van, and away downstream. We would have to refill the tank, either in San Luis in the morning or directly from the stream. Then I began to move our provisions from under the rear seat to the passenger seat in the front.

While Tom and the men with shovels continued to dig, other men gathered dry branches to place under the tires. The children crouched near the van door and watched wide-eyed as I moved our ample supply of canned goods and fresh produce. I joked with them, saying, “Una tienda” (a store). My rudimentary Spanish, mainly nouns and hand gestures, made the children laugh. I was having fun, though in the back of my mind I wondered if we would be spending the night in the middle of a Mexican river.

By this time, half a dozen men had come to our aid, and the work was almost finished. Most of the water was diverted away from our tires, and the workers placed rocks and branches under them. The children and I squatted on the dry bank and watched as our men labored together.

When Tom felt all was ready, he motioned for the digging to stop. “Alto!” he said in the limited Spanish he remembered from high school. “Suficiente. Esta terminado.”

He climbed into the driver’s seat, and six men laid their hands on the back of the van. They strained against the vehicle with their combined strength while Tom pushed the gas pedal. Suddenly, with a lurch, the van was up the embankment and again on dry land. The children and I cheered and clapped our hands. The local diggers, covered in mud and sweat, grinned. Tom, as dirty and mud-spattered as the others, jumped out of the van cab and shook hands all around.

There was no way to sufficiently thank these Mexican villagers, but Tom and I, in broken Spanish, did our best. We had a bottle of red wine in our stash, which we presented to the men, and I handed out all the bananas and oranges from our “tienda” to the children.

Dusk had passed, and the cloudless sky was dark by the time we reached the highway. When our wheels were firmly on pavement again, we turned back to the campground we had rejected earlier that afternoon. Tom, who looked more like a golem made of mud than a man, luxuriated in a hot shower at the camp bathhouse while I prepared dinner and refilled our empty water tank.

By morning, the entire experience had taken on the rosy glow of a treasured memory. As we drove down the highway, the men in the fields looked familiar. Tom honked the van horn three times, an audible toot to get their attention. Our friends looked up from their fieldwork and waved their arms in recognition. Tom and I waved back in both greeting and goodbye.

These were the first friends we made on our trip. Locals and fellow travelers in far-flung places like Spain, Sicily, Norway, Iran, India, and Nepal would become our instant, short-term friends in the many months to come. Sometimes they helped us, and sometimes we helped them. Other times we simply enjoyed the company of strangers for an hour or a few days. Regardless of whether we learned their names or never heard from them again, they remain part of the fabric of memories from our road trip about the world.

*

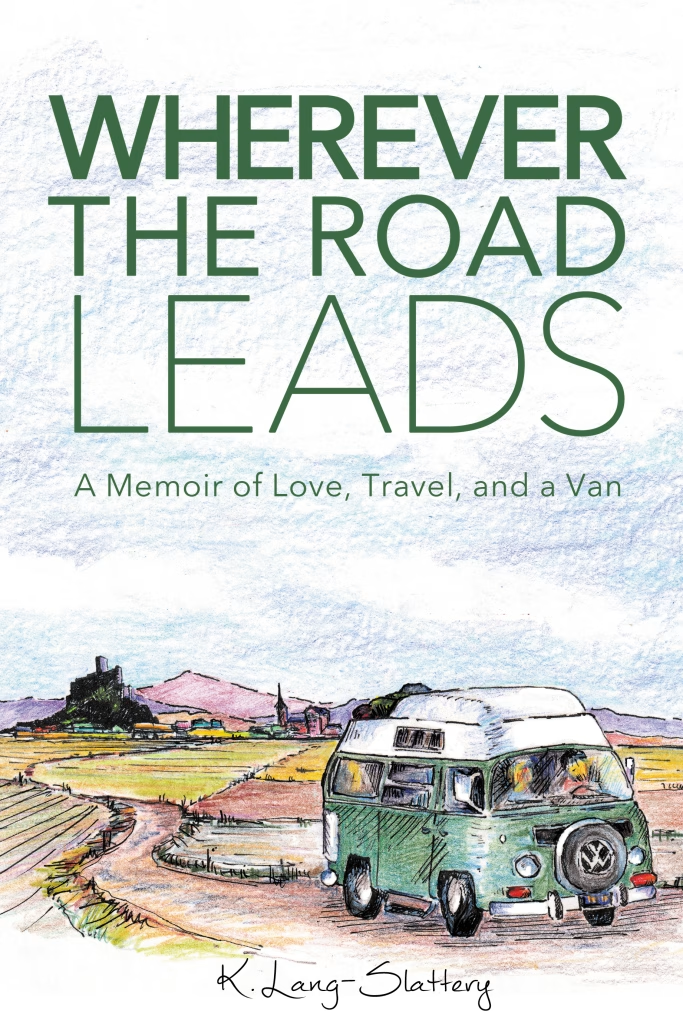

The Help of Strangers is an expanded and reworked excerpt from my memoir, Wherever the Road Leads.

Available at a discounted price for a limited time through this exclusive link.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply