2001 Continues

By the third afternoon, our tour group arrived in Agra. My second visit. Una’s first. Our guide, Prakash, warned us we would start before dawn the next morning. Ten hours later, the Elderhostel group stood in awe as the shrouded form of the Taj Mahal floated in and out of gray mist. When the ethereal curtain lifted, the golden glow of sunrise illuminated the white marble, and the reflecting pool shone silver.

Prakash smiled mysteriously. “The best will come this evening,” he said.

Before dinner, we all piled into several white Morris Minor taxis. They sped through alleys, bumped over ruts, and lurched around sacred cows, oxcarts, and pedestrians. We entered a village of thatched houses and dirt lanes, our drivers tooting at every intersection. At the end of this wild ride, we walked across a hillocky expanse of white sand toward the Jumna River. In the distance, smoke and flames rose from a cremation ground. The scents of burning wood, incense, and river damp filled the air.

On the far embankment, the Taj Mahal stood regally, its dome and minarets reflected in the steel-blue water of the river. Gilded by the setting sun, the tomb shifted from gold to amber, from amber to mauve, and to the deep blue of evening.

The following day, our bus rumbled westward along the Delhi highway headed to Rajasthan. In 1972, Tom and I drove eastward on the same road, traveling toward the capital city of New Delhi.

Back then, the two-lane road was undergoing massive roadwork, and our progress was continually slowed by work gangs and detours. Many of the laborers were women dressed in long, full skirts, the bright colors dulled by dust. They carried baskets of stones on their heads or squatted in the dirt to break rocks into gravel using a hammer and chisel.

Our modern bus boasted a folding “sidekick” bench in the cab near the driver and the doorman. I eagerly claimed the jump-seat for much of the trip, and from this favored vantage, the view transported me back in time. Little had changed other than that the road was no longer being repaired.

The two lanes were thick with trucks, black sedans, and carts pulled by ancient tractors or plodding, long-legged camels. Loaded with anything from logs of acacia wood to sacks of grain, the carts rolled along on rubber truck tires. Cart drivers sat with one leg tucked under them and their loose sarong-like dhotis pulled up to expose brown legs. In the villages, people gathered at community water pumps. Women filled water jugs or recycled cooking-oil tins and gracefully lifted them to their heads, while men in drenched dhotis bathed under the same taps.

At the end of a long day on the bus, we entered Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan. Our hotel overlooked a lake and the surrounding hills―a clear upgrade from van camping in the 1970s.

Our tour of the city began at the “Clock Tower” morning market, where an elephant, his mahout astride his shoulders, sauntered through the crowds of shoppers and porters. Their presence here seemed as normal as an SUV in the States. Stacks of fresh vegetables and mounds of colorful spices in the open stalls made me long for my microbus kitchen, where I had first experimented with Indian cooking.

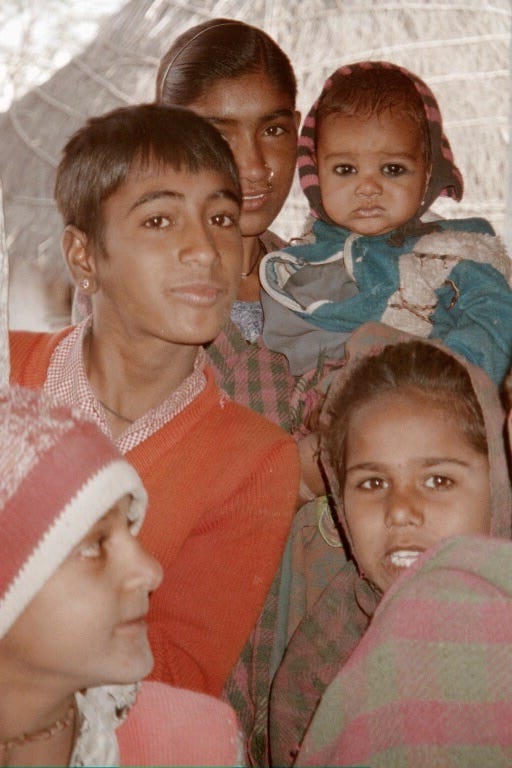

Two days later, in Jodhpur, sometimes called the “Blue City” of Rajasthan, we took jeeps across the dry countryside to a weavers’ and potters’ enclave. A parade of waving children and adults greeted us. The village elder, his thick glasses held together with tape, escorted us to a weaver’s home where the artisan sat at a pit-loom sunk into the brown earth. His shuttle flew as he created colorful sari fabric. At the potters’ workshop, we watched a bone-thin man build huge clay jugs by hand, then sat on rugs in the community center and listened to local music. We visited the village school, a wide dirt space surrounded by low walls, without a schoolhouse. A canvas awning strung between the wall and a single tree provided the only shelter. Within the square of shade it cast, the children sat on the dirt reciting their lessons. When they finished, they clustered around our group, laughing and holding out their hands for our gifts of pencils and pencil sharpeners.

Several days later, we left Rajasthan and flew to the Mumbai (Bombay) airport. It was already evening when Una and I bid the group goodbye. They were going home, but we were about to embark on a week of independent travel. We located our guide, who waited at the crowded arrivals gate with a piece of cardboard on which my name was scrawled. He hustled us to a taxi and out into the crowded city.

The mid-class hotel I had booked was on the Mumbai waterfront. We knew it would be several steps of luxury down from the places we had been staying with the group. When we neared the harbor, I recognized the Gateway of India, a monumental arch built to commemorate King George V and Queen Mary’s 1911 visit to India. Its black silhouette stood sentinel at the water’s edge, backed by the moon-sparkled Arabian Sea. Just beyond a public park of spreading mango and banyan trees, we stopped in front of a three-story building with a single light and a blinking neon sign.

An old man led us to a tiny elevator that clanked loudly as we rose upward. We found ourselves on a flat roof filled with tables and chairs and a bar counter at one side. Our porter led us to a rough stucco cube and fumbled with the lock in a wooden door. He waved for us to enter, handed me the key, turned, and disappeared.

The room, probably originally servants’ quarters, was not more than eight feet square with barely enough space to walk around the one double bed. A hard-backed chair stood in the corner. A narrow wooden board, a kind of counter, was nailed below the single window that opened onto the café/bar. In the minuscule bathroom, a water pipe jutted out of the wall without a showerhead or an enclosure. The 1970s Volkswagen microbus offered more comfort than this cubicle.

“We can’t stay here,” I told Una. “I’ll go downstairs and beg for a better room. Wait here.”

The clerk yawned behind his desk. “The room is too small for two women with big luggage.” I said, determined to save face with my older sister.

The clerk looked glum. “Nothing else available.” He wagged his head.

“If you have nothing, you must help me find a better room at another hotel. We will not stay in the room on the roof!”

With another sidewise, Indian-style head shake, the clerk lifted the phone. His voice was agitated, and his Hindi incomprehensible. When he hung up, he smiled. “I have something for you,” he said. “Much better room, but not ready for guests. You please wait.”

“I’ll get my sister,” I said.

“Yes, yes, Memsahib. Meet me on the third floor in ten minutes.”

It was obvious the better room had been a lounge for the hotel employees. Two men and the clerk scurried about, straightening the bedcovers, dumping the waste containers, emptying ashtrays, gathering up dirty teacups and water glasses, and removing used towels. But the room was big; there were two full-sized beds, a decent bathroom, and a door that opened onto a tiny balcony overlooking the street and the harbor. Exhausted, we didn’t care that the wrinkled bedspreads were probably soiled and dust balls lingered in the corners. We fell asleep as soon as our heads hit the lumpy pillows.

Early the next morning, I awakened to loud cawing. Una stood on our little balcony. Already dressed in nylon shorts for her morning run, she held a mug of coffee in her hand and looked out to the water of the harbor. I joined her. Ten or twelve large crows circled over a nearby mango tree, making a racket. Below in the street, a scrawny monkey scurried along the docks.

We loved our east-facing balcony. If we woke early enough, we could witness the silver of the sea bleeding into the gray of dawn. The orange morning sun emerged in a sudden burst, its fiery orb casting a molten path of reflected light leading to our window.

After a few days in Mumbai, Una and I plunged into India in earnest. We took a chugging narrow-gauge train into the hills and spent several days in Matheran, a “no cars allowed” hill station resort. We wandered the dusty roads to gaze into rocky gorges and across jungle-covered hills. There was little to see besides scores of begging monkeys, sari-clad women, schoolgirls insalwar kameez uniforms, horses available for rides into the hills, and stands selling snacks at the various viewpoints.

The evening before our departure, we were invited to tea by our hotel hosts, Mr. Lord and his diminutive wife. “We have train tickets to Pune,” I explained to them. “We’re excited to visit Sangam, the Girl Scout/Girl Guide World Center.”

Mr. Lord asked about our tickets. “Local Indian trains stop at every village along the route,” he told my sister and me. “It will take six hours to get to Pune.”

Mrs. Lord pulled the pallu of her sari around her shoulder and refilled my teacup. “You must take the Konya Express train,” she said. “Otherwise, the journey will be long and hot.”

The next morning, we stood on the hotel veranda and gazed at the view of mountains cloaked in morning mist. In front of the lodge, two rickshaws waited, each pulled by a pair of scrawny men.

We soon understood why two men were needed to control the cumbersome rickshaw. The descent to the valley was steep and twisting. As we jostled down, groups of pack mules and teams of chanting construction workers pushing carts loaded with bricks headed up. Everything―from people to food, from construction materials to trinkets―arrived in Matheran by foot, by mule, by cart or rickshaw, or on the “toy-train” we had taken to get there.

When we arrived at the lowland train station, Una and I went directly to the ticket window. “No first-class seats on the express,” the clerk told us. “All sold. Only second-class tickets, Memsahib. No reserved seats. Standing only, maybe.”

We put our heads together. “A few hours of discomfort,” I said. “Better than an all-day train ride.” Surely, I thought, we two Girl Scouts could handle a couple of hours traveling second-class in India.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply