Part 1

Jawaharlal Nehru: “India is a geographical and economic entity, a cultural unity amidst diversity, a bundle of contradictions held together by strong but invisible threads.”

1972/73

Almost fifty years ago, I was on the Hippie Trail with my new husband, traveling overland to India and back. The huge subcontinent of India was the final segment of our two-year honeymoon. Our green Volkswagen microbus, nicknamed The Turtle, was both home and transportation. Tom and I slept every night in our cozy van, never leaving it for a hotel or hostel. I cooked all our meals on a two-burner butane stove. A lidded bucket served as our commode. Indian Public Works Department gardens, villages of sand and palm trees, open fields, side roads, and back streets were our camping spots.

We arrived at the India/Pakistan border in the deep hours of a December night. Tom and I were exhausted after a 500-mile, day-and-a-half drive from Kabul, Afghanistan, where we had spent a week waiting for our Indian and Pakistani visas. India would be a welcome respite after Afghanistan with its endless, empty spaces and tales of camel-riding bandits. In 1972, India’s western border with Pakistan was only open at one place for twelve hours each week. We did not want to miss the opening.

Late the night before that day, Tom wedged our van between two giant trucks in the unlit waiting area near the border. “The noise of the trucks starting their engines in the morning will wake us,” Tom assured me before we crawled into our comfortable bed in the back of the van.

A soft tap on our window startled us awake the next morning. We peeked between the curtains and looked out at an empty expanse of dirt. A teenage boy pointed to a bridge in the distance where hundreds of trucks and a few cars formed a line that inched toward the border barrier gate. “Oh, my god,” Tom groaned, “we’re going to be at the end of the line.”

We finally made it into India in the late afternoon, only an hour before the border shut down for the next seven days.

Once in India, I couldn’t wait to buy my first sari. As a teen, I had learned how to wrap the garment from an aunt who had lived in India. I was eager to dress like the local women and show respect for their culture. By the next afternoon when we visited the Golden Temple in Amritsar, I was draped in a sari, my waist-length blond hair twisted into a discreet bun.

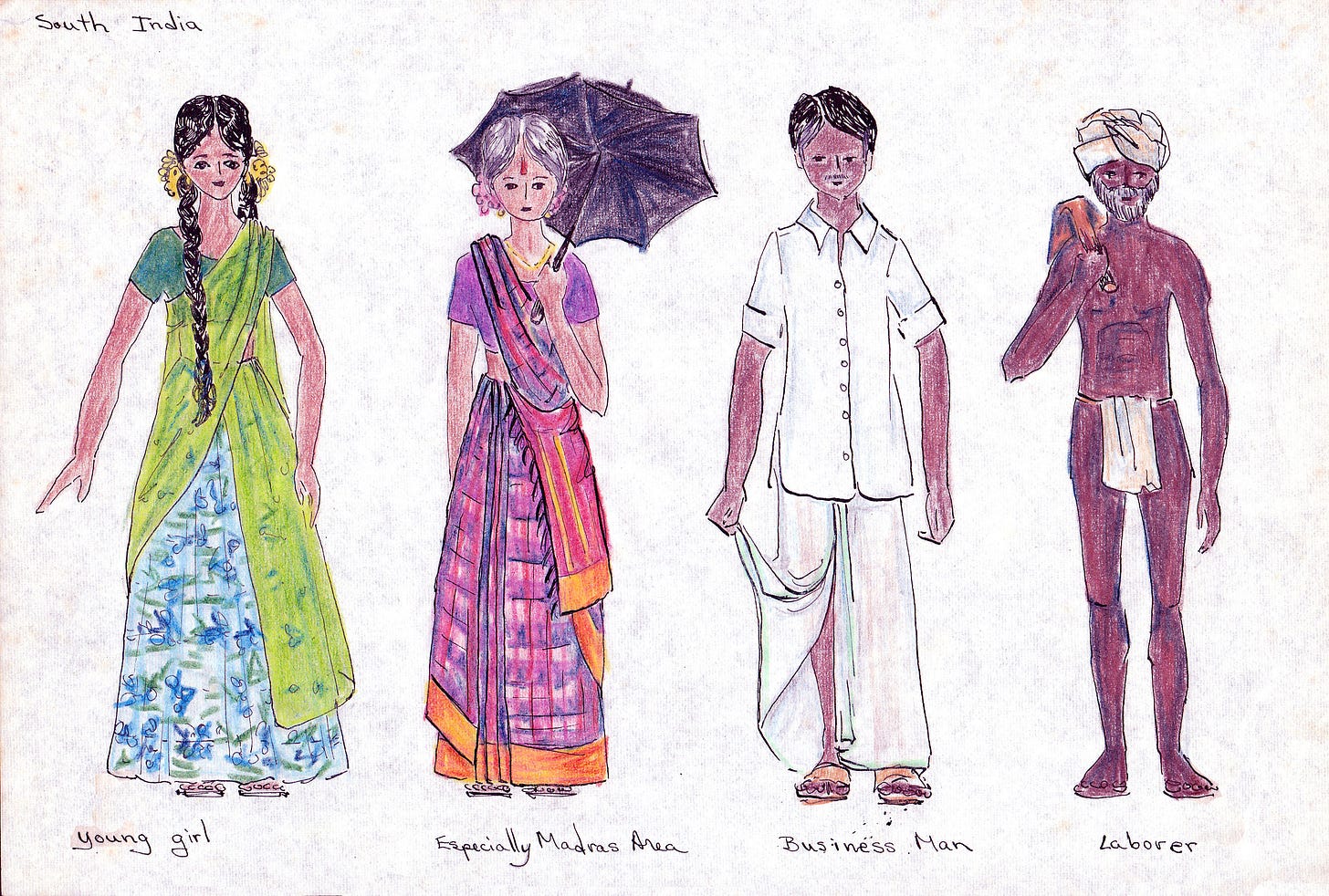

In less than a month, I possessed a collection of close to a dozen saris. I became fascinated by the different ways the women wrapped their flowing garments—slight variations from region to region, from city to village—and I drew colored-pencil studies of the changing styles.

Our Indian visa was good for four months―enough time, we hoped, to see India. Tom and I greeted every new sight with the joy of being together. The energy of youth pushed us to create memories that would last. We sat in awe and gazed at the white marble splendor of the Taj Mahal and rode in a rowboat on the river Ganges, past men in lungis and sari-clad women dipping into the sacred waters. We visited Madras on the Bay of Bengal and the Cardamom Hills, where tea and spices grew. We spent a week in a beachside fishing village in Goa on the coast of the Indian Ocean, and after a few days in Bombay, we drove into the dry, dusty central plateau, heading for the legendary land of the Rajput Maharajas.

As we crossed the drought-plagued lands north of Mumbai, our dream hit a speedbump. My throat began to burn painfully, and I quickly developed a high fever. Our plans to visit Rajasthan, with its arid desert and exotic splendors, evaporated. My temperature soared, and Tom passed the road to Rajasthan. He turned instead toward New Delhi, where he could find a Western-educated doctor for me.

As I recovered in Delhi, our Indian visas inched toward expiration. With only three days left, we agreed to tackle a final Indian excursion. If not Rajasthan, why not Kashmir? The twisting, two-lane dirt road to Srinagar was used mainly by Indian army vehicles, which regularly drove up and down, bringing troops to secure the contested border between Kashmir and Pakistan. Tom steered the van carefully around washouts, landslides, and a makeshift bridge of two boards suspended over a bottomless chasm. I clung to my seat. If we die here, I thought, at least Tom and I will go together. After one restful day in the high mountain paradise, we headed to the Khyber Pass and the long road back across Afghanistan, Iran, and through the troubled Middle East toward Europe. But the disappointment of missing Rajasthan lingered.

2001

Twenty-eight years later, my sister mentioned she wanted to visit India, but none of her friends were up for this exotic destination. Una was five years older, and we were not particularly close, but she was also an intrepid traveler. Why not join her? I thought.

“As long as we can visit Rajasthan,” I said, “I’ll go with you.”

Una and I made plans. We would travel with Elderhostel (now called Road Scholar) for two weeks, then plunge into India on our own to visit a hill station. Because we had both been Girl Scouts in our youth, the Girl Scout World Center in Pune would be our grand finale.

Based on my past India experience, Una suggested I take charge of our week of independent travel. I was unsure how van travel in 1973 prepared me for booking hotels and trains in 2001, but I tackled the assignment with as much confidence as I could muster.

Of necessity, Una and I flew separately to India. I landed at Indira Gandhi International Airport late on a night in January. The dirty, noisy arrival hall was crowded with Indian travelers and confusing signs. The room seemed to shout, “I am India! Remember me?”

I shouldered my travel-pack and located the taxi counter. A tall, handsome Sikh manned the desk. His distinctive turban and neatly groomed beard, characteristics I had learned to trust in the 1970s, reassured me. He wagged his head, took my money, and waved me toward the exit door.

The sidewalk outside the terminal was crowded with touts aggressively soliciting customers for their extraordinary services. My Sikh led me to a jeep-like vehicle at the front of the taxi line. A slight man with a woolen scarf wound around his neck loaded my bulky pack into the back. Another man jumped into the driver’s seat while the Sikh helped me into the cramped passenger space, my daypack still securely slung over my shoulder. I repeated the name of the hotel, and all three men wagged their heads. The Sikh spoke to the driver in rapid-fire Hindi, or maybe it was Punjabi or Urdu, and we were off!

The main road outside the airport was devoid of streetlights. The traffic lanes were congested with blunt-nosed black cars, a few white luxury sedans, jitneys, and loaded trucks. We zipped along, squeezing between lumbering lorries and the center divider of broken concrete. My driver gleefully beeped his horn each time he wedged his jeep between two moving vehicles, all bigger than his jitney.

In the glare of passing headlamps, I observed the man who held my safety in his hands. He was wiry, with greased, combed-back hair and a well-trimmed mustache. Friendly and curious in a way I knew to be typical, he asked if I was traveling alone, if I was single, and if my hotel was expensive. Beyond that, he concentrated on navigating the chaotic traffic.

Gradually, the congestion thinned, then disappeared. Dark emptiness stretched into the distance where pinpoints of light glinted. Nothing suggested a busy city. Would I be stripped of my luggage and money and abandoned, far from help? I clutched my daypack to my chest. Memories of safe passage on similar lightless Indian roads thirty years before kept me calm.

Finally, a roadside stand selling tandoori chickens and a vendor of Bengali sweets appeared out of the darkness. The sight of a helmeted scooter-driver, his female passenger riding side-saddle behind, reassured me. The lady clung to her companion’s waist, her sari flowing in the air currents, hinting at romance and normal family life.

Suddenly, my driver pulled his jeep to the far left and waited for a break in traffic. Across the road, I saw one light, an old wall with a wide gate, and behind it, my hotel. My name was in the front-desk ledger, and a porter led me upstairs to a room with a huge bed, a desk, a wooden wardrobe, a lumpy couch, and a spacious, tiled bathroom.

I settled on the bed and reached for the phone to order tea from room service. When I accidentally nudged the bedside lamp, a shower of sparks erupted. An instant later, all the lights in the room died. I leaned back against the pillow and sighed. This was India. This time, rather than sharing a romantic odyssey with my new husband, I would be on a journey with my sister.

The next morning, Una arrived in time for the first day’s introductions and a tour of the Red Fort.

Thirty years before, Tom and I spent an entire afternoon wandering the same fort. We bought samosas from a vendor near the gate and munched on them as we explored. It was still stunningly beautiful in 2001, but my excitement was generated more by memories of the red ramparts and marble columns seen through an earlier romantic lens than by the guided group experience.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply