After a late night, Una and I began our first day on our own in India very slowly. I spent what seemed like hours on the phone booking a driver and guide for the next day. We arranged for an Elderhostel friend, a lady who also stayed a few extra days in Mumbai, to join us. Una, an accomplished marathon runner, donned her shorts and went for her mandatory daily run. Her habit gave me dependable alone time to read or shower without interruption. Some days I even walked behind her as she trotted along. By noon we were both ready for lunch at the Taj café. Remembering pleasant lunches Tom and I had eaten there years before, I ordered “my usual,” the fillet of Pomfret. It arrived as delicate and tasty as in my memory!

After lunch, eager to share more places I had enjoyed in the winter of 1973, I suggested we visit the sprawling Crawford market. As soon as we got out of the taxi, Una and I were enveloped by crowds of shoppers. Two middle-aged Western women, we soon attracted the attention of one of the ever-present touts. Though some of these guys can be pleasant enough companions, this one was truly obnoxious. We tried to discourage him in the bluntest way possible, but he wouldn’t leave. He claimed he was a government employee and it was his duty to stay with us. Finally, fed up with the guy’s lies, Una turned to me and said, “Let’s go find a policeman and ask if it’s true.” Instantly, our unwanted helper melted into the crowd and was gone. How powerful we felt—we had coped with a typical travel problem all by ourselves.

Sightseeing was on the top of our agenda the next day. Our hired car and a young woman guide who spoke perfect English took us to all the notable sights. The alleyway that led to the Temple of Ganesh was filled with stalls selling flower garlands. At the Gandhi Museum, we saw the room where Gandhi slept and his spinning wheel. We stopped briefly at Hanging-Gardens Park and then drove near the Parsi Towers of Silence, where the Zoroastrian dead are laid in the sun and devoured by birds of prey.

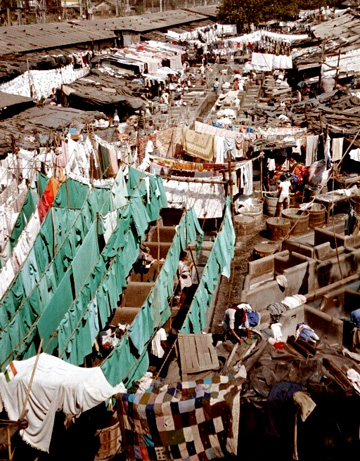

Our last stop was a view overlooking the river and the dhobi ghats. This 140-year-old, open-air laundromat hummed with activity. An estimated half-a-million pieces of laundry from hospitals, hotels, and homes are hand-washed there each day. Dozens of washer-men, each with his own concrete station, scrubbed linens and clothing, spun the wet laundry in manual dryers, and pressed out the wrinkles with charcoal filled irons.

By a stroke of good luck, Una and I had an invitation to lunch on our last day in Mumbai. We were invited to the home of a middle-class Indian family who were relatives of a member of my California writing group. On the morning of our visit, we dressed in our best (Una in a new shalwar kameez), bought a box of chocolates as a hostess gift, and set off by taxi, train, and tuk-tuk to the suburbs north of the city.

My friend’s nephew, Sachin Patel, met us at a local shopping area. Dressed in khaki slacks and a western-style shirt, he was a solid young man with a round face, a mustache, a sliver of a goatee, a friendly smile, and near-perfect English. He led us on foot to a green stucco building of indeterminate age and the small, second-floor apartment where he lived with his mother, Jyoti, his wife, Kavita, and their happy, chubby-cheeked, black-eyed, baby. The two women, both dressed in extra-nice shalwar kameez, also spoke excellent English. Their much loved, first-born son wore a little cotton shirt and a diaper the size of a hanky. He sat on his mother’s knee and babbled quietly while the adults talked.

Sachin, a designer, worked at home creating web-sites for international companies. Kavita, who had lived in Florida for four years and worked as the assistant manager for a large Miami hotel, now stayed home to care for their baby. Our hosts were easy to talk to, knowledgeable and modern, and curious about our experiences in India. After we had talked for a while, Jyoti and Kavita excused themselves to put the baby down for his nap and dish up the prepared lunch.

The women returned to the sitting room with individual thali plates (round, rimmed metal plates) brimming with the yellows, browns, greens, and reds of an Indian meal. Each bite was better than the one before—crunchy okra seasoned with coriander; a thin, slightly-sweet dhal of yellow lentils; cauliflower, cabbage, and carrot salad; sweetened, thick yogurt topped with saffron and pistachios; hot mango pickle; peas with mint; and paratha, a tender, fried, flat-bread. We ate perched on the sofas, probably because our hosts figured that American ladies wouldn’t be comfortable sitting on the floor, the usual way for Indian families to gather for meals.

I’ve always liked to eat food the way it’s eaten by the locals. I use chopsticks for Chinese food and, when in Europe, I keep my fork in my left hand and lift it backwards to my mouth. So, in India at the Patel’s home, I used the fingers of my right hand to gather up the curried vegetables, pickles, and bread. Only the thin dhal stumped me and I resorted to a discreetly placed spoon to make sure I got every drop. At the end of the meal, Kavita served squares of carrot halva, a sweet, cardamom-laced, pudding made by cooking grated carrots, milk, butter, and sugar together. I had actually made this dish at home myself so I knew it involved hours on low heat, stirring constantly until all the liquid milk evaporated and the ingredients came together into a bright orange mass.

I had read in a guide book that when visiting an Indian family, it was polite to stay only thirty minutes or so after a meal. So, after a half an hour, Una and I said we needed to go. The Patels seemed genuinely disappointed that we must leave and gave us parting gifts of small Ganesh shrines. As we stood to go, Sachin asked, “Where will you spend the rest of your time in India?”

Una mentioned that she had always wanted to visit a hill-station so we planned a trip to Matheran, located in the hills east of Mumbai. I said that we would also take the train to Pune because I wanted to visit the Girl Guide World Center located in that city.

“Oh, yes,” Jyoti said, “I know of the Center. I was a Guide when I was a girl.”

Kavita chimed in. “I also was a Girl Guide. I loved wearing the beautiful blue uniform with the scarf around my neck.”

It was already late afternoon when we made it back at our hotel. Though we were not really hungry after our lunch, Una and I were determined to try a nearby kabab stall on our last night in Mumbai. The popular food stall took over the alley behind the Taj Hotel every evening after regular business hours when it was allowed to set tables in the street. In spite of being tired, we quickly packed our bags for the next day and walked to the kabab restaurant.

In the gathering darkness, crowds filled the road near the open-air restaurant. Strings of electric light bulbs cast a yellow glow over the area. One cook concentrated on spinning and stretching dough to make paper-thin flat-bread. The dough circles, about the size of a two-person pizza, were cooked on the back of an over-turned kadai, a wok-like cooking pan. Two more sweating cooks stood over a long, metal, out-door cooker filled with red-hot coals. They turned whole chickens splayed open Tandoori-style, as well as, skewers of marinated chicken chunks, ground lamb, and chopped vegetables mixed with spices. A fourth man assembled the meals to order. He filled round sheets of warm bread with the meat of choice, a few slices of raw onion, and a scoop of chutney. The bread was rolled around the filling to form folded “sandwiches” which he put on a tray.

We watched customers place their orders with a man who held a huge book of pink, receipt slips. A young boy delivered each order to the customer with a receipt, collected the rupees, and brought the money back to the cashier. Una and I copied what we saw, placed our order, and found a tiny table among others arranged in the street. Our Chicken Tikka rolls arrived steaming hot and fragrant with spices. Each cost less than a US dollar. My only regret was that I was unable to eat a second one.

Our stay in Mumbai would soon be over. . . . . the next day we would tackle the Indian train system.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply