2001 Continues

Una and I had a decision to make. A longer, more comfortable trip versus a faster trip in an Indian second-class train car. I was inclined to experience traveling like a local. Van travel and Girl Scout backpacking taught me I didn’t always need luxury to enjoy a journey. Una was older, but this was my second trip to India, so she deferred to me. “I can do it if you can,” she said.

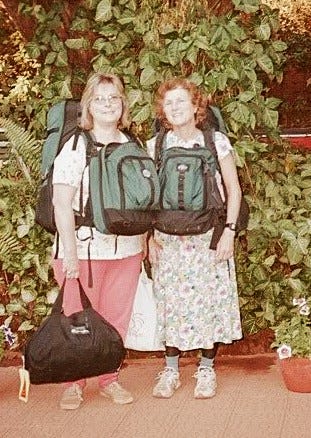

Tickets in hand, we waited for the Konya Express. When it arrived, Una and I―two middle-aged, white women―each with a twenty-five-pound-plus travel-pack on our back and a bulging daypack across our chest―pushed and shoved up the stairs with the other boarding passengers. The entire car was filled with local village people. No other western travelers greeted us.

Every inch of floor and seat space was packed. Sari-clad women crammed together four or five on facing wooden benches. Men stood shoulder to shoulder, between the seats and over-flowed into the aisles. In the corridor, several farmers in crumpled, white dhotis and threadbare business shirts sat on string-tied baskets bulging with produce. An old woman in a tattered sari squatted on her haunches between two of the facing benches.

Seriously encumbered by our travel-packs, Una and I squeezed into a space between stacked luggage and the sandaled feet of several men. Una sighed, took her backpack off, and wedged it between her legs. I kept mine on. Experience on European public transport had taught me it was sometimes better to keep the pack on despite its weight. We began to move. I planted my feet to balance myself and my heavy load.

The train swayed along the track like a boat on an ocean. We were surrounded by a sea of humanity. We struggled to stay upright as passengers constantly shoved up and down the aisle. Each time someone passed, we had to shift our position. Amidst all this flowing traffic, I was glad I had kept my pack on my back. I only had to turn and pivot to allow people past. Time after time without complaint, Una, visibly stressed, lifted and moved her pack.

Despite being an express, the train stopped frequently. Passengers got on and off, causing the masses to shift and reassemble. Vendors shouldered their way through the aisle selling snacks, fruit, bottled drinks, candy, and toys. Between stations, they called out to attract buyers, then jumped off at the next stop, while another group climbed aboard. Once, a blind beggar climbed up the stairs and walked through the string of cars, chanting and holding his hand out for coins. A young assistant led him through the maze of people and baggage, ensuring he did not stumble.

As time passed, the weight of my pack pulled on my shoulders. Two young men smiled and gestured. “Too heavy, lady. Too heavy for you,” one said. The other tried to help me remove my pack. But I shook my head stubbornly. They shrugged and got off at the next stop. Two men and a young woman came to take their place. Una had gratefully eased herself into the narrow space left by a scrawny old lady who had hobbled off the train.

As we neared Pune, more passengers left than arrived. Several people pushed closer together to make room on the hard wooden benches. An old man, his head topped by a wound cloth, patted a narrow spot next to him. “Here. Sit, Lady. Sit,” he said.

Gratefully, I took off my pack, sat, and leaned against the wooden backrest. Una perched across the aisle wedged between two women, one with a sleeping baby in her arms.

We arrived in Pune in mid-afternoon and the relative comfort of a tuk-tuk taxi took us to the waiting luxuries of the Girl Scout world. At Sangam, we were greeted by a blonde lady dressed in a blue Guide uniform, her British accent music to our ears. She showed us our room, pointed out the showers and WC, and invited us to tea in the dining room. Among these familiar comforts, our train journey evolved into an amusing travel story.

In a second-class train car, we―two American ladies, one fifty-five and the other sixty―had met local India head-on and survived. We couldn’t wait to share our adventure on the Konya Express with our new English friends.

2024

Twenty plus years later, I was in India again—once more surrounded by sari-clad women and head-shaking men. No longer twenty-eight as when I first set foot in India nor fifty-five as on my second trip, I now traveled with a cane, two steel knees, a C-pap, blood-pressure meds, a cochlear implant, wheelchair assistance at all airports, and my adult daughter, Erin. Neither Volkswagen living nor group travel were my style at eighty-two. I had discovered the pleasure of an air-conditioned car with a driver and a local guide. Luckily (for I am at heart a budget traveler) throughout most of Asia this is affordable, sometimes even less expensive than an organized group tour.

Both drawn to Asian food and culture, Erin and I enjoyed traveling together. In the preceding years, we had been to Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos. Erin grew up listening to my tales of traveling in India with her father in the early 1970s. Now she was ready to see it for herself.

When she suggested India, I agreed on condition we visited the southern states where I hadn’t been for fifty years. Hyderabad, which sits on the central plateau at the southernmost border of what was the Mughal Empire, proved the perfect place to greet India for the first time (Erin) and the third time (me).

Eager to plunge headlong into the heat and crowds, we met our guide in the hotel lobby. Tall and stocky, Jalil greeted us with a welcoming smile under his bushy black mustache. He introduced himself as a professor of ancient Indian history. Our driver navigated the clogged streets while Jalil talked about Hyderabad. Erin gawked out the windows, following my finger pointing to remembered sights ― the traffic, the roadside vendors, and the buildings jumbled incongruously, old against new.

I marveled at the number and variety of motor vehicles. Now, besides trucks and jitneys, the streets were clogged with private cars of all colors and makes. The ever-present, three-wheeled tuk-tuks, a cross between a motorcycle and a rickshaw, sported color-coded placards to indicate if they were powered by gasoline, natural gas, or electric batteries.

Once out of the city congestion, dusty, fallow fields lined the two-lane road and villages clustered in the distance. There were no oxcarts or camel-carts in sight. Heavy-duty tuk-tuks puttered along, carrying loads of hay, manure, and pumpkins.

Our first stop was an enclave of ikat weavers. Fifty years before in 1973, the technique of dying threads before weaving them into patterned fabric had fascinated me and I bought two ikat saris.

In the demonstration room of the Ikat museum, Erin and I watched a weaver at work. His loom, like the one I had seen in Jodhpur in 2001, was suspended over a pit. Below the level of the floor, his feet worked the treadles, and above, his hands shuttled the dyed weft threads back and forth.

Behind the cultural center, we entered a quiet street of weavers and dyers cottages. Skeins of dyed thread hung from the rafters of one porch. In front of another home, the sidewalk was decorated with an elaborate chalk pattern we were told was created by the housewife each morning as a kind of meditation. Jalil explained that the designs brought positive energy, and the beauty and complexity of the pattern expressed the artist’s feelings that day.

In a nearby village, we visited a dyer at work. We removed our shoes and tip-toed around the chalk design on his doorstep. Inside a tall man in a dhoti sat on the tile floor working on lengths of white threads staked out in front of him. He demonstrated how he tied strands tightly together at established intervals with narrow strips of inner-tube rubber.

Nearby his wife heated dye in several iron pots set over charcoal fires. When her husband finished his work, she would dye the threads. Wherever he had secured his rubber strips, the color did not penetrate, leaving white areas that would later form a pattern in the woven fabric.

In mid-afternoon, we stopped at an open-air roadside restaurant, a popular place with wooden plank tables under a thatched roof.

Jalil said he had ordered a traditional South Indian vegetarian repast for us. We were each given a thali, a round steel tray topped with a banana leave cut to fit. Our table was soon covered with small bowls, each with a different kind of runny stew we were told to call “gravy.” There were several types of curried vegetables, curd (thin yogurt), fiery-hot mango pickles, and a plate of puffy, crisp papadums. The waiter arrived with an immense bowl of steamed rice and deposited scoops of the white grains onto our thali. Jalil showed us the proper way to eat with our right hand, using the tips of our fingers. Erin and I quicky got into the spirit. We ladled gravy, swirled the flavorful concoctions into our rice, ate with relish, and occasionally licked our fingers surreptitiously.

After lunch, at our request, Jalil took us to a shop selling scarves and fabric. An hour later, with a bulging bag of purchases, we headed back toward the city. Erin, continually curious, asked questions, including personal ones about Jalil’s family and education. In response, he explained that, as the eldest son of a traditional family, he was responsible for finding brides for his several nephews. “I prefer,” he said, “to get them wives from the countryside―girls less likely to be influenced by modern city ways.” We were surprised that a well-educated college professor would be so old-fashioned, but he was, after all, a man who chose to specialize in ancient Indian history.

In Hyderabad, Jalil had one more treat for us―the 17th century Makkah Majid.

“Your heads must be fully covered,” he said, “or you will not be allowed to enter the mosque forecourt.”

My neck-scarf covered my hair, but Erin’s was too narrow, so Jalil bought her a blue, star-studded scarf at a nearby stall. The gate guard allowed us into the courtyard, but even with our scarves, as women and nonbelievers, we were barred from the holy interior.

The bustling square outside the mosque’s gate was crowded with young people who gathered to talk, drink tea, and eat snacks. Surrounded by jostling and friendly youth, we stood at a tall table, sipped hot Chai, and tasted an assortment of cookies and a luxurious fried confection filled with whipped buffalo cream (malai).

After stuffing ourselves with sweets, we wove our way through the crowds to our waiting car. At the hotel, we fell into our beds with no need for supper.

And this was only our first day!

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply