After five days in Northern India seeing the iconic sites of the classic Mogul emperors, we headed west. Finally, I would see Rajasthan. The largest state in India, it hugs the Pakistani border and much of it consists of the inhospitable Thar Desert. Once the home of the Rajput maharajas, Rajasthan literally means “the land of Kings.”

In the early morning of our sixth day in India, we boarded a bus and set off for Jaipur, the state capital. Tom and I had journeyed along this same road on our way to Delhi in 1972. At that time, the two-lane highway had been undergoing improvements and I remembered the women who labored there. Dressed in long, full skirts, the bright colors dulled by dust, the women carried baskets of stones on their heads or squatted in the dirt as they broke rocks into small pieces with a hammer. Now the highway was broader and the pavement smooth. Still the shoulder consisted mainly of dry dirt, concrete rubble, or ditches filled with weeds.

Our bus was comfortably roomy for our group, but its best feature, in my view, was a kind of “side-kick” folding bench on the left of the ample cab. In the morning, several members of the group spent a few minutes there in order to snap photos of the passing traffic. In the afternoon, satiated by a good lunch and groggy with the heat, my fellow travelers were content to stay in their seats where they napped, read guide books, and watched India through the smudged windows. For the entire afternoon, I reigned as queen of the jump-seat, sitting up front with the driver and the “door-man.”

From my perch, I had a clear view of the road ahead and on both sides. I wondered what I would see that was different from those earlier days . . . or if I would find it much the same. The cab was hot and the bench was hard and offered no back-rest, yet I loved every minute. Outside the window, India was on display, the sights both exotic and familiar to me. I found myself transported back to that first trip and I felt the same excitement and wonder I had experienced when I was twenty-nine.

Here are some of the sights I saw:

- Lots of camel carts. They roll ponderously along on large rubber truck tires and carry loads of all kinds—everything from logs of Acacia wood to sacks of grain. The cart drivers sit on the front of the cart with one leg tucked under them, their loose sarong-like dhotis pulled up to expose brown legs. Camel carts lumber along, pulled by the long-legged beasts at a plodding pace. Once we stopped in traffic with a cart so close I could nod and wave at the turbaned mahout.

- Also, lots of tractors pulling loaded carts. The heavy, farm vehicles seem to have replaced many of the bullocks and water-buffalo we saw on the roads in 1972. I wonder, do tractors now pull plows or is that work still the purview of animals?

- Skeletons of several large cows. Their carcasses, picked clean by dogs and buzzards, lie in a roadside ditch, the bare ribs sticking up above the weeds.

- Men and women gathering at water pumps near their village entrance. The women collect water in jugs and recycled cooking-oil tins. They lift the heavy containers gracefully to their heads and carry them home. At the end of the work day, men in water drenched dhotis lather up under the same taps. They rinse off by dumping buckets of clear water over their heads. These late-afternoon rituals seem unchanged.

I was still enjoying my special seat when we entered Jaipur. The bus climbed a narrow road lined with old buildings where court musicians used to play whenever the Maharaja arrived in the city. Our hotel overlooked a lake and the surrounding hills . . . . a clear upgrade from van camping in PWD enclosures. We only stayed a day in Jaipur but that day was filled with sightseeing, highlighted by an elephant ride up the steep entrance to the Amber Fort.

A brief early morning flight brought us to Jodhpur and more sightseeing and lectures, including one about the desert ecosystem. We learned about trees that can go thirty years without water, the importance of livestock (mainly sheep, goats, and camels), and grains, like millet, that need little water and also produce animal fodder.

The rest of the week was filled with the sights and smells of Rajasthan I had longed to experience.

At the “Clock Tower” market, stacks of vegetables and hills of spices filled the open stalls. I missed my microbus kitchen that would have allowed me to buy supplies and cook a meal. The market was crowded with shoppers and porters. Once we had to step aside to allow a lumbering elephant to pass.

At the “Clock Tower” market, stacks of vegetables and hills of spices filled the open stalls. I missed my microbus kitchen that would have allowed me to buy supplies and cook a meal. The market was crowded with shoppers and porters. Once we had to step aside to allow a lumbering elephant to pass.

One morning, we drove in jeeps across dry countryside to a weavers’ and potters’ enclave.

As we approached the village, our line of vehicles was joined by a parade of children and adults who waved and shouted greetings. The village elder, his thick glasses held together with tape, greeted us formally. He took us to a weaver’s home where the artisan demonstrated his pit loom sunk into the ground. At the potters’ workshop, we watched a bone-thin worker form huge jugs by hand. We sat on rugs in the village center and listened to a music performance.

Later we visited the local school, little more than a wide dirt space surrounded by low walls of dried mud. In the middle stood a concrete-topped cistern. A small awning jutted from one wall to create a patch of shade. The children, all dressed in white shirts and red skirts or shorts, sat in the dirt of the dusty rectangle to recite their lessons. At the end of a lesson, the children clustered around us, laughing and holding out their hands. I gave out handfuls of pencils I had brought from home for this purpose.

On the bus trip between Jodhpur and Udaipur, we stopped far from any village. We tramped along a narrow pathway, across a dirt field, and past an ancient waterwheel. A group of colorfully costumed local singers, musicians and dancers waited for us near a spreading Khejri tree. There, surrounded by farmland, we enjoyed a performance of drums, lutes, and dancing girls. As the dancers swayed, their vivid saris swirled in the hot air and the gold threaded borders sparkled in the sun. The tinkle of tiny cymbals attached to the dancers’ fingers and feet accompanied each graceful movement.

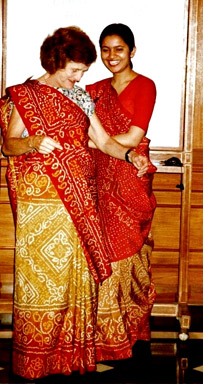

In Udaipur, at a hotel more elegant than our usual, we enjoyed a sumptuous banquet. An after-dinner lecture explained traditional clothing and how dress reveals a person’s background, education, and class status in Indian village culture. Our beloved guide, Prakesh, demonstrated how to wrap a man’s turban and dhoti. A young woman from the hotel showed how to wear a sari, using Una as the mannikin. The next evening, after shopping at a huge store filled with fabrics and art, Una and I dressed up for the group’s farewell dinner. She wore a newly-purchased sari and I sported my new, custom-fitted, blue cotton shalwar kameez (basically a long tunic over ballooning pants).

We parted from the Elderhostel group in Bombay. Soon Una and I would be traveling on our own in India. I was confident we were ready.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events and personal insights from Katie Lang‑Slattery.

Leave a Reply